Nature: Why did the world's biggest ape go extinct?

Gigantopithecus blacki was the largest ape that ever lived, and might have gone extinct because it could not adapt when its environment changed.Credit: Garcia/Joannes-Boyau (Southern Cross University)

The world’s biggest primate might have gone extinct because it couldn’t reach the most nutritious fruits, according to a study published today in Nature1. The paper also offers clues on why the giant ape’s contemporary, an ancient orangutan, continued to thrive almost 300,000 years ago as the environment changed.

With an estimated height of 3 metres and weighing a hefty 200–300 kilograms, Gigantopithecus blacki was the largest primate to ever roam Earth. Anthropologist Ralph von Koenigswald discovered one of the ape’s massive teeth in a Hong Kong apothecary nearly 90 years ago. Since then, researchers have unearthed four jawbones and roughly 2,000 more teeth in caves scattered across China — but no other parts of a skeleton have been found. The scant fossil evidence has made it notoriously difficult to build an accurate picture of G. blacki, let alone the circumstances that led to its disappearance, says study co-author Kira Westaway, a geochronologist at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. “We just don’t know much about it,” she says.

To solve the mystery of its extinction, Westaway and her colleagues analysed fossils and sediments from 22 caves in Chongzuo and Bubing Basin in southern China. They used six dating methods to find the exact timeframe of G. blacki’s demise, and reconstructed the giant ape’s environment in the period before it went extinct using a range of techniques — such as pollen analysis and investigating sediment layers under a microscope. The researchers also analysed chemical traces in the enamel of G. blacki’s teeth to investigate how its diet changed over time, and compared these signatures with those seen in the teeth of its close relative Pongo weidenreichi, an extinct orangutan that lived alongside the giant ape.

Their work revealed that G. blacki disappeared between 295,000 and 215,000 years ago, slightly later than previously estimated (420,000–330,000 years ago)2. During G. blacki’s heyday some 2.3 million years ago, the landscape was blanketed by dense forests with the odd patch of grassland. When the researchers analysed G. blacki’s teeth from this period, they found several distinct bands of various trace elements. The clearer and more distinct these bands are, the more trace elements the teeth contain, which means that the giant ape was eating a wide variety of foods and drinking plenty of water.

But from around 700,000 years ago, pollen analysis showed that the landscape began to change, with forests becoming more open as the seasons changed more drastically. By this time, G. blacki’s teeth showed more-blurred bands, a sign that it was forced to consume a less nutritious, more fibrous diet as its favourite forest foods and water sources became scarcer. The researchers also found fewer G. blacki fossils during this period, indicating that populations were dwindling.

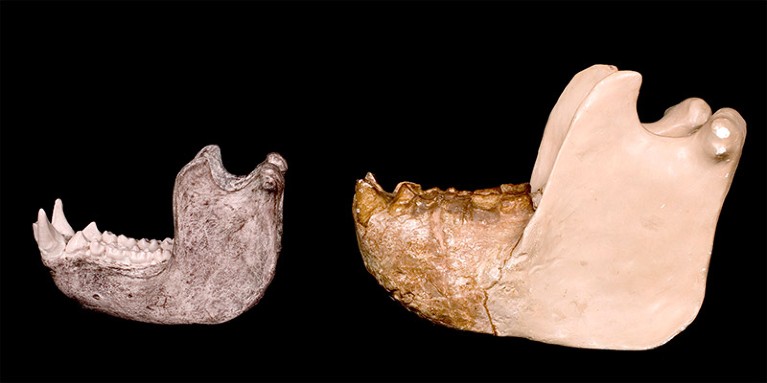

A gorilla's lower jaw bone (left) and a reconstruction from a fragment of a Gigantopithecus blacki jaw bone (right).Credit: Natural History Museum, London/Science Photo Library

On the other hand, the teeth of the tree-climbing P. weidenreichi continued to show relatively clear banding, suggesting that it adapted to the changing environment with greater ease than its ground-dwelling relative.

Westaway suspects that the orangutan might have climbed trees to grab foods that were out of reach for G. blacki. The fossils also showed that G. blacki grew in size during this time, whereas P. weidenreichi became smaller, making it more nimble than the massive ape, she adds.

Between 295,000 and 215,000 years ago, G. blacki was nowhere to be seen in the fossil record whereas P. weidenreichi was still found to be relatively abundant. The thick forests that once supported the giant ape had become sparse during this time , with open grasslands and ferns dominating the ancient landscape.

The study provides the most precise picture of the circumstances around G. blacki’s extinction to date, says Hervé Bocherens, a palaeobiologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. But he adds that more fossils need to be found to improve body-mass estimates, which would allow researchers to better understand the giant ape’s dietary needs and what made it more vulnerable to change than other herbivores in the forest.

Westaway and her team are on the hunt for more G. blacki fossils, particularly its thigh bones, which would give researchers a better idea of its size and biology. “There’s still a lot more evidence out there,” says Westaway. “It’s just trying to find the right cave.”

Nature 625, 433-434 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00033-8

Download attachments: