Global Times: Fossils show Jurassic ancestors of 'underwater vampire' actually flesh-eating, not blood-sucking

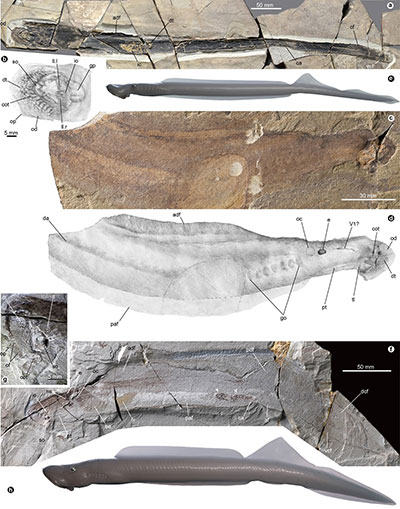

Photo: Courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Living jawless fish, especially lampreys, have become a highly studied animal group for evolutionary developmental biologists and ecologists and are even regarded as a model for research in vertebrate evolutionary biology.

It is because jawless fish may potentially preserve clues about the deep origin of important organs - the jaws of vertebrates and the paired fins (like the limbs of terrestrial vertebrates), and have a significant impact on modern fisheries.

The lampreys, dubbed "underwater vampire" and the prototype of monsters in thriller movies, has a "horrifying mouth and feeding behavior." They also have a three-stage life cycle, similar to the transformation of a tadpole into a frog. Through metamorphosis, the lamprey larvae develop into adults with significant differences in morphology and ecology, including fundamental changes in feeding behavior.

The discovery of large lamprey fossils from the "Yanliao Biota," a treasure trove of fossils from the Jurassic period, provides important clues to answer questions about how modern lamprey evolved to have this unique feeding behavior and what impact this had on the evolutionary history of lampreys, the Global Times learned from the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology on Friday.

Photo: Courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

The fossils were collected by Wang Xiaolin and Wang Min, research fellows with the institute. The institute's research fellows Wu Feixiang and Zhang Chi cooperated with professor Philippe Janvier at France's National Museum of Natural History on the research, which was published in Nature Communications online on Wednesday.

The lampreys have no hard bones in their bodies, and their teeth are made of keratin, making it difficult for them to be preserved as fossils. However, the lamprey fossils found in the Yanliao Biota not only remain intact, but most importantly, their suckers and teeth are preserved in almost three-dimensional states, providing rare and valuable samples for understanding the evolution of lamprey feeding behavior.

The new materials include two species of lampreys, Yanliaomyzon occisor (Yanliao killer lamprey) and Yanliaomyzon ingensdentes (Yanliao giant-toothed lamprey). The Yanliao killer lamprey is over 64 centimeters long, making it the largest known fossil lamprey. Most Paleozoic lampreys are only a few centimeters long, with the largest ones measuring around 10 centimeters, even smaller than the near-metamorphosis size of modern lamprey larvae. Larger-sized lampreys have been reported in the Cretaceous Jehol Biota, but no material with a body length exceeding that of the Yanliao killer lamprey has been reported.

The tooth structure of the Yanliao lamprey is very different from today's common lamprey in the Northern Hemisphere, such as the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), but shares many similarities with the pouched lamprey (Geotria australis) that currently inhabit the southern hemisphere's Australia, New Zealand, and southern Chile.

Their suctorial disc teeth and the teeth used for cutting meat are also very similar, indicating that these Jurassic lampreys, like the pouched lamprey, are typical flesh-eating lampreys. The presence of bone fragments in the digestive tract of Yanliao lamprey fossils also confirms this.

The relatively complete morphological information for the Yanliao lamprey, including its teeth, reveals its phylogenetic relationship with other lampreys. Using Bayesian total evidence dating and phylogenetic analysis methods, this study reconstructed an updated time tree of the lampreys. The analysis results show that the Yanliao lamprey (Yanliaomyzon) is the closest fossil ancestor of modern lampreys known to date.

The feeding habits of modern lampreys are diverse. The blood-sucking species, such as the sea lamprey, are the most well-known, while fewer kinds are carnivorous. There are also species that feed on carrion or do not feed after metamorphosis. Different feeding habits correspond to different dental characteristics.

The previous belief was that the ancestor of the modern lamprey was a blood-sucking type similar to the sea lamprey. However, the research analysis and ancestral state reconstruction of the Yanliao fossils indicated that the ancestor of the modern lamprey is more likely to be a carnivorous species.

According to the time tree and researchers' deductions, since the Jurassic period, the feeding system and ecological habits of the lamprey have been close to those of modern lampreys. But there have been changes in the food sources for the lampreys.

It has been speculated that since the early Jurassic period, more advanced and thin-scaled bony fish have appeared in large numbers, providing a plentiful food source, leading to an increase in their body size and energy needs.

Modern lampreys' "anti-tropical" distribution is a very interesting biogeographical conundrum. Today, nearly 90 percent of the lamprey species live in the northern hemisphere, and the blood-sucking lampreys in the northern hemisphere are considered to be from more primitive lineages. Therefore, it is generally believed that the northern hemisphere is the birthplace of modern lampreys.

However, the latest research proposes a different explanation - based on the reconstruction of the time tree, modern lampreys may have originated in the southern hemisphere in the Late Cretaceous period (about 78 million years ago) due to the constraints of Jurassic lampreys. During the early Cenozoic period (approximately 58 million years ago), the north and south lampreys diverged and after the late Oligocene, the northern hemisphere species expanded from the north Pacific region to the north Atlantic region.

The divergence occurred later than previous studies suggested, meaning the "living fossil" lampreys may not be as old as expected.

Download attachments: