A young giant panda eats bamboo in the Chengdu Research Base of the Giant Panda Breeding Center in China.

Photograph by Jak Wonderly, National Geographic Creative

In August 2014, paleoanthropologist Yingqi Zhang and his team descended into a sinkhole on the hunt for Gigantopithecus, the largest known primate to ever live. They came back out with a mix of bones from the hapless creatures that had fallen into the natural "death trap."

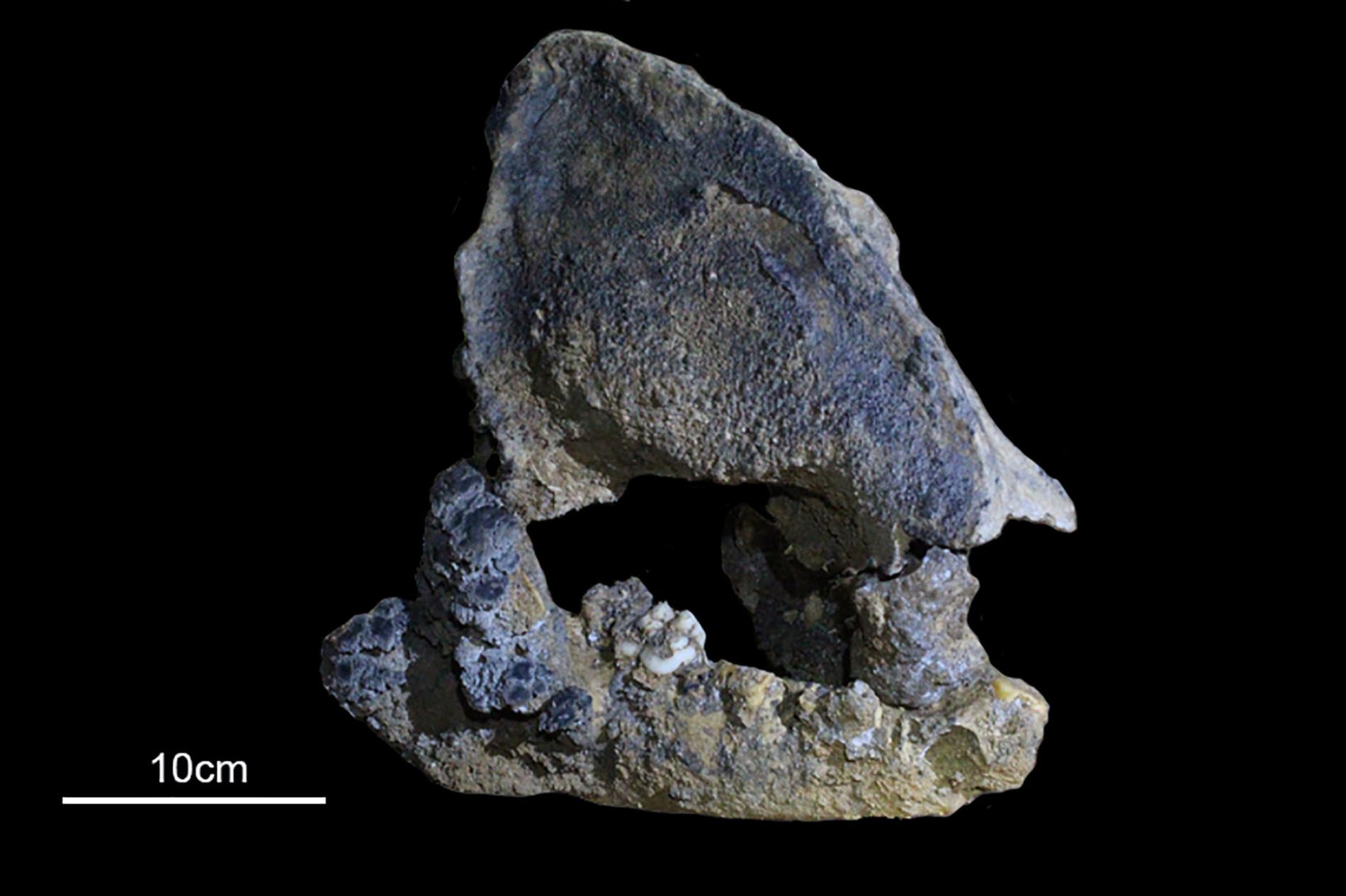

None of those bones belonged to the extinct ape, but the team was in for a surprise: The mix included a 22,000-year-old lower jaw from an ancient panda. And within its worn edges, the jaw held what is now the world's oldest sample of panda DNA.

With just a single fossil, it’s too soon to call the creature a new species. But the genetic evidence shows that the bone belongs to a previously unknown lineage of giant panda that split from its other panda cousins about 183,000 years ago.

This fossil jaw comes from a giant panda relative that lived 22,000 years ago.

Photograph by Yingqi Zhang and Yong Xu

This animal may have been specifically adapted to living in its subtropical home, suggesting that the black-and-white beasts were once much more diverse than they are today, the authors argue in a paper published today in the journal Current Biology.

While the conclusions about panda diversity may not be revolutionary, the team’s work extracting ancient DNA from the degraded fossils is significant, says Russell Ciochon, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Iowa in Iowa City who was not involved in the study.

"We not only opened the possibility to get ancient DNA from a quite hot place, but also [from bones that are] quite old," says geneticist and study coauthor Qiaomei Fu, who led the genetic analysis of the samples.

Hidden Genetic Treasures

Modern pandas lumber across a tiny range in just three provinces of central China: Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu. But they were likely once widespread. Researchers have found fossil panda fragments across China, Myanmar, and northern Vietnam, and as far away as Hungary and even Spain.

When Zhang and his team recovered the bones from Guangxi Province in southern China, they were thrilled to find ancient remains of the beloved symbol of China in an area where the beasts have long since gone extinct. But from a glance, the fossil looked similar to modern pandas. And since it was just a fragment of fossil—and not a complete skull—they didn’t pursue further study. Besides, Zhang was focused on the hunt for Giganto.

So for a year and a half, the fossil sat in a corner of Zhang's office at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, wrapped in toilet paper and stowed in a plastic box.

Fu, who is also a researcher at the academy, meanwhile had been attempting to extract panda DNA from other fossils for several years to no avail. The heat and humidity of southern China breaks down the delicate swirls of DNA, making the task extremely challenging.

Researchers at China's giant panda breeding centers have discovered how to encourage captive pandas to mate, how to make sure the pregnancy is successful, and how to keep the panda cubs alive once they've been born.

Her first attempt at analyzing the new panda fossil was also unsuccessful. "But I insisted on trying again," says Fu.

The team CT scanned the fragment to make sure they aimed for a snail shell-shaped structure in the inner ear called the cochlea, which is known for its stellar DNA preservation in humans. The redo was worth it: This time, the team was able to sequence the panda’s complete mitochondrial genome.

It was an exciting achievement, says Fu, who describes the data as "quite special information."

Fuzzy Futures

The results from this paper jive with another recent study of panda DNA recovered from two southern China fossils, one around 5,000 years old and the other nearly 8,500 years old. The oldest of the pair also appears to be a "sister" to modern pandas, splitting off from the shared line some 62,000 years ago.

The pair of studies adds to the slowly growing genetic database of ancient giant pandas, says Robert Fleischer, head of the Center for Conservation Genomics at Smithsonian's Conservation Biology Institute, who was not involved in the work.

"It would be really interesting to compare them directly," Fleischer says of the sister species and the newly found lineage. Such a comparison could help confirm the identity of the fossils and determine any potential adaptations the ancient beasts had to the subtropical climate.

Fu plans on trying to extract full nuclear genomes from the fossils, since that type of data could tell scientists a lot more about the creatures beyond their family relations. Perhaps they could even get more information about extinct pandas’ looks, including whether the animals were always so black and white.

Fu and her team will also continue to analyze the mitochondrial DNA of panda fossils, hoping to fill in the blanks on the panda family tree. After all, she explains, better understanding the panda’s past may yield ways to help protect its future.