Nature:Teeth from China Reveal an Early Human Trek out of Africa

These 47 human teeth, dated to 80,000-120,000 years ago, were found in a limestone cave system in Daoxian, China. Credit: S. Xing and X-J. Wu

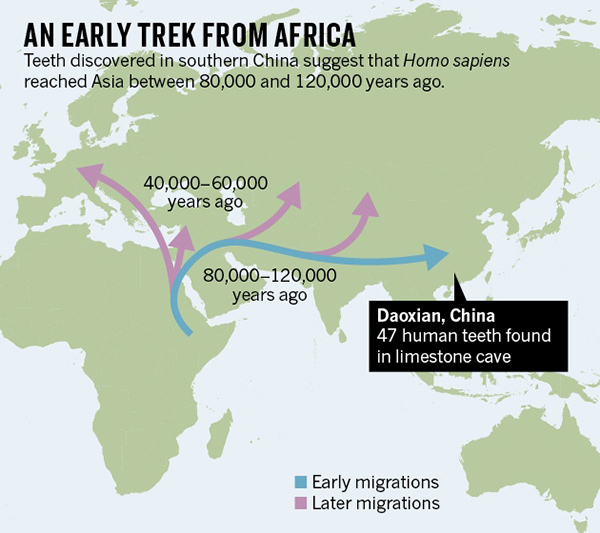

Teeth from a cave in south China show that Homo sapiens reached China around 100,000 years ago—a time at which most researchers had assumed that our species had not trekked far beyond Africa.

“This is stunning, it’s major league,” says Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford, UK who was not involved in the research. “It’s one of the most important finds coming out of Asia in the last decade.”

Limestone caves pockmark Daoxian County in Hunan Province, China. Recent excavations of a cave system there extending over 3 square kilometres discovered 47 human teeth, as well as the remains of hyenas, extinct giant pandas and dozens of other animal species. The researchers found no stone tools; it is likely that humans never lived in the cave and their remains were instead hauled in by predators.

The teeth are unquestionably those of H. sapiens, says María Martinón-Torres, a palaeoanthropologist at University College London who co-led the study with colleagues Wu Liu and Xie-jie Wu at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. Their small size, thin roots and flat crowns are typical for anatomically modern humans—H. sapiens—and the overall shape of the teeth is barely distinguishable from those of both ancient and present-day humans. The team report their results in Nature today.

Determining the age of the teeth proved tricky. They contained no radioactive carbon (which has almost vanished after 50,000 years). So the team dated various calcite deposits in the cave and used the assortment of animal remains to deduce that the human teeth were probably between 80,000 and 120,000 years old.

Early trekkers

Those ages buck the conventional wisdom that H. sapiens from Africa began colonizing the world only around 50,000–60,000 years ago, says Martinón-Torres. Older traces of modern humans have been seen outside Africa, such as the roughly 100,000-year-old remains from the Skhul and Qafzeh Caves in Israel. But many researchers had argued that those remains were only evidence of unsuccessful efforts at wider migration.

“This demonstrates it was not a failed dispersal,” says Petraglia, who has long argued for an early expansion of modern humans through Asia on a southerly route. “This is a rock-solid case for having early humans—definitely Homo sapiens—at an early date in eastern Asia.” Chris Stringer, a palaeoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who had argued that remains from Skhul and Qafzeh signified unsuccesful migrations, says that he is now swayed by the Daoxian teeth.

Without DNA from the teeth, it is impossible to determine the relationship between the Daoxian people and other humans, including present-day Asians. But Jean-Jacques Hublin, a palaeoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, thinks that later waves of humans replaced them. Other genetic evidence sugests that present-day East Asians descend from humans who interbred with Neanderthals in western Asia some 55,000–60,000 years ago, Hublin notes.

It is also not clear whymodern humans would have reached East Asia so long before they reached Europe, where the earliest remains are about 45,000 years old. Martinón-Torres suggests that humans could not gain a foothold in Europe until Neanderthals there were teetering on extinction. The frigid climate of Ice Age Europe may have erected another barrier to people adapted to Africa, says Petraglia.

Although Hublin says there is a good case that the Daoxian teeth are older than 80,000 years, he notes that several of the teeth have visible cavities, a feature uncommon in human teeth older than 50,000 years. “It could be that early modern humans had a peculiar diet in tropical Asia,” he says. “But I am pretty sure that this observation will raise some eyebrows." Martinon-Torres says her team plans to look more closely at the cavities and the diet of the Daoxian humans by examining patterns of tooth wear.

Southern China is filled with similar caves that may colour in more details of humans’ early exploits, such as the tools they made. “This is just the tip of the iceberg,” Petraglia says. “There’s a lot more work that needs to be done."

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 14, 2015.

Download attachments: