| Location: Home > Research > Research Progress |

| Unique Early Cretaceous bird from China provides window into the early evolution of birds and flight |

|

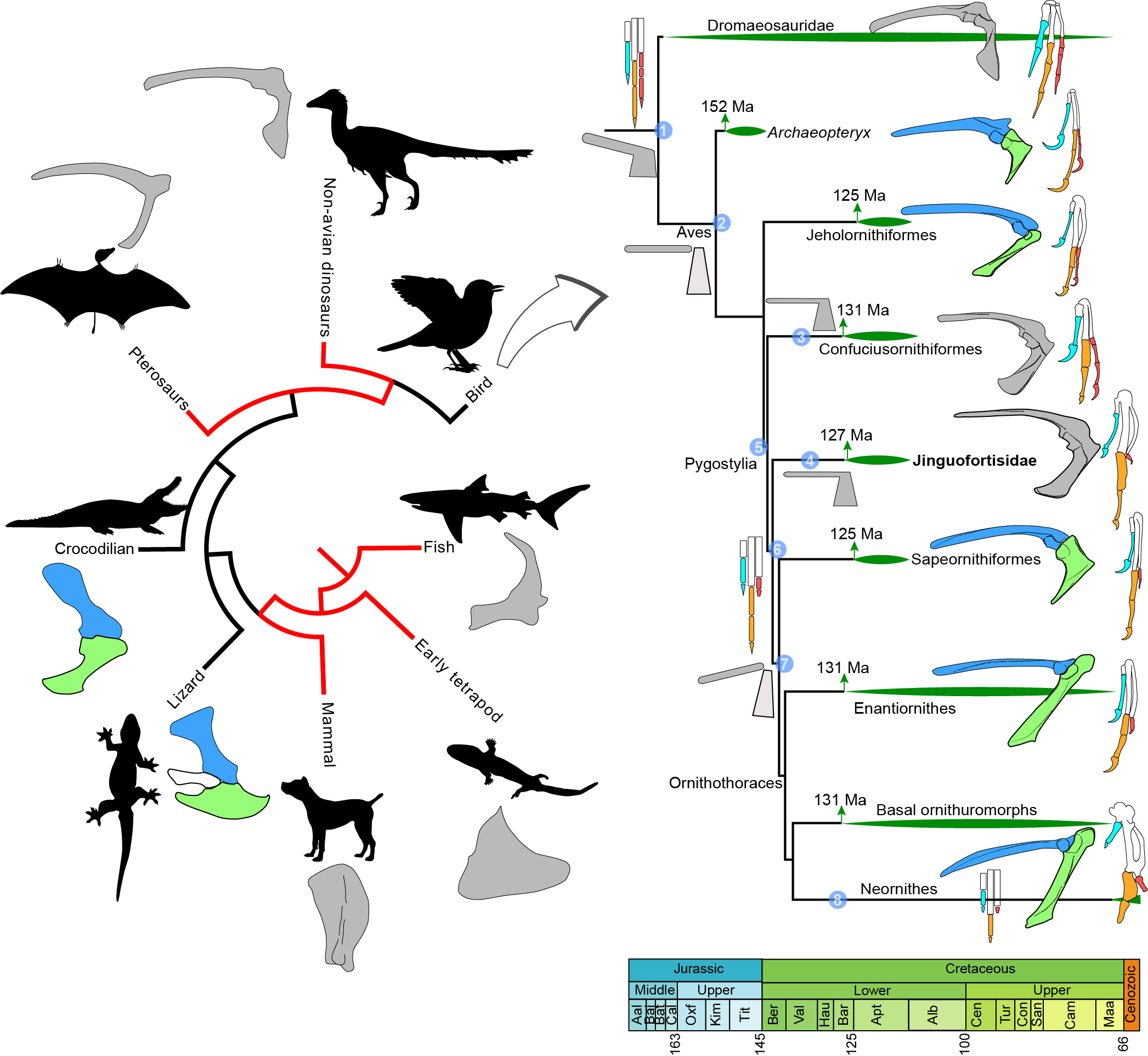

A new extinct species of bird from a 127 million-year-old fossil deposit in northeastern China provides new information about the different evolutionary paths and experiments birds experienced during the early evolution of flight. Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Drs. Min Wang, Thomas Stidham, and Zhonghe Zhou of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing detail their study of the well-preserved complete skeleton and feathers of this early bird. The evolutionary analysis of this fossil bird demonstrates that it is from a pivotal point in the evolution of flight where birds had lost their long bony tail, but before they evolved a fan of flight feathers on their shortened tail. Dr. Wang and his collaborators have named this extinct species Jinguofortis perplexus. The genus name “Jinguofortis” represents a dedication to women scientists around the world, and derives from the Chinese word “jinguo” (巾帼), meaning female warrior, and the Latin word “fortis” meaning brave. In the evolutionary history of birds and flight, Jinguofortis perplexus, together with another less well-known Chinese bird fossil called Chongmingia zhengi, form the second most primitive bird group with a short bony tail. To recognize that status, Dr. Wang and his coauthors have named a new family Jinguofortisidae to include both species. This bird fossil from the early Cretaceous period has a unique combination of traits. Dr. Zhou says, “This fossil bird has a jaw with small teeth like their theropod dinosaur relatives; a short bony tail ending in a compound bone called a pygostyle (that evolved after the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx); gizzard stones showing that it mostly ate plants; and a third finger with only two bones in it (unlike other early birds).” About the importance of this new species, Dr. Stidham says, “Generally we think of the modern flight apparatus of living birds as having evolved through the gradual accumulation of refinements to their feathers, muscles, and bones over millions of years. However, this new bird fossil shows that the evolution of flight was much more messy.” The shoulder joint experiences high stress during flight, and it is a very tight joint between unfused bones in the shoulder girdle in flying birds. This spectacular fossil preserves a fused shoulder girdle where the major bones of the shoulder, the shoulder blade (scapula) and the coracoid, are fused to one another, forming a scapulocoracoid. A scapulocoracoid is common among theropod dinosaurs and living flightless birds, like the ostrich. However, this extinct species clearly was capable of flight based on analysis of its very long and asymmetrical wing feathers and its skeleton. The only early birds known to have a scapulocoracoid are the newly recognized Jinguofortisidae and another common early Cretaceous bird group from China, the Confuciusornithiformes. “Birds secure the shoulder girdle and joint between the scapula and coracoid in a variety of ways. Some have a peg on one bone that fits into a socket on the other, and some birds have those features reversed. This fossil shows a different way of doing it, by fusing the two bones into one. With that fusion, these early birds probably were trying to make their shoulder joint more secure and to fly the best they could,” says Dr. Wang. The occurrence of a fused shoulder girdle in these early short-tailed groups suggests that birds during this stage of evolution experimented both with different ways of growing their skeleton, and using their flight apparatus. Combined with all of the features of the skeleton and feathers, Jinguofortis perplexus probably flew a bit different to how a typical bird does today.

Figure 1. A 127-million-year-old fossil bird, Jinguofortis perplexus (reconstruction on the right, artwork by Chung-Tat Cheung), second earliest member of the short-tailed birds Pygostylia. Credit: Min Wang, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Figure 2. Major changes of the coracoid and scapula (main components of the shoulder girdle) across the major vertebrate groups; the right is a simplified cladogram shows the phylogeny of Mesozoic birds with highlights of the changes of the shoulder and hand. Credit: Min Wang, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. |