| Location: Home > Research > Research Progress |

| A Tandem-Horned Rhino From the Late Miocene Of Northwestern China Reveals Origin of the Unicorn Elasmothere |

|

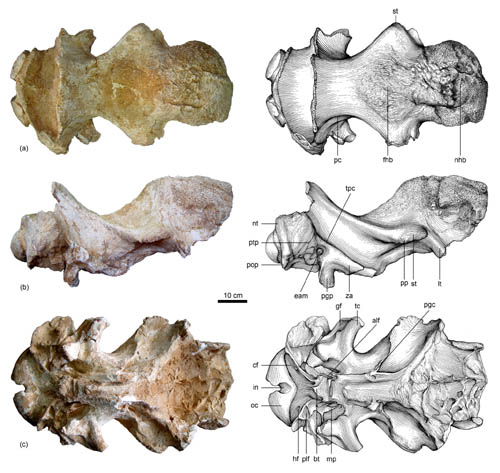

Transition of a nasal horn to a frontal horn in elasmotheres has been difficult to explain, because a major transformational gap exists between nasal-horned ancestors and frontal-horned descendants. In a paper published in May 2013 in the journal of Chinese Science Bulletin (Vol. 58, No. 15), Dr. DENG Tao from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his colleagues reported the first discovered skull of Sinotherium lagrelii from the Late Miocene red clays with an age of about 7 Ma in the Linxia Basin, northwestern China. This skull has an enormous nasofrontal horn boss shifted posteriorly and a smaller frontal horn boss, which are connected to each other, providing new evidence on the origin of the giant unicorn Elasmotherium.

Although the modern Indian and Javan rhinos have a single horn on their noses, the extinct one-horned rhino Elasmotherium was a source for the legendary unicorn, because it had a two-meter-long horn on its forehead and lived with the prehistoric human beings who drew its images on cave paintings. All other elasmotheres have a weak or strong nasal horn, whereas Elasmotherium seems to lose the nasal horn of its ancestors and to get a huge frontal horn apparently abruptly.

This new skull is an intermediate stage for the single frontal horn of Elasmotherium. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses confirm that Sinotherium is a transitional taxon between Elasmotherium and other elasmotheres, positioned near the root of the giant unicorn clade and originated in a subarid steppe. The posteriorly shifted nasal horn has a more substantial support and the arched structure of the nasofrontal area is an adaptation for a huge horn.

Previously, S. lagrelii was represented by some cranial and mandibular fragments and isolated teeth from the Late Miocene deposits in Baode County, Shanxi Province, China as well as Kazakhstan and Mongolia, so its horn situation was unknown. S. lagrelii is the closest to the Pleistocene Elasmotherium in dental morphology, but the nature of its frontal horn has not been determined. This skull proves that S. lagrelii has a posteriorly shifted nasofrontal horn, derived from the condition seen in early elasmotheres, and a smaller frontal horn, so it is different from Ningxiatherium with a single nasal horn and Elasmotherium with a single frontal horn, but it is a morphological intermediate in the nasal-to-frontal horn transition of elasmotheres and builds a connection for the evolution and biogeography of the derived elasmotheres.

The nasofrontal area ofthe skullis strongly elevated and rough to form a huge and hollow dome, in sharp contrast to the flat and smooth area in large nasal-horned elasmotheres, such as Iranotherium, Parelasmotherium, and Ningxiatherium. This reduces the weight of the nasal and frontal bones. The nasal horn boss is shifted posteriorly to reach the frontal bone and to connect to the frontal horn boss, and such a horn combination has not appeared in any other extinct or extant rhinoceros. The dorsal surface of the horn bosses has many massive swellings in order to strengthen the adhesion of a huge nasal horn and a smaller frontal horn, and the ventral surface has an ossified sagittal septum and many oblique lateral ribs to form a trussed structure in order to enhance support like the leaf structure of the giant waterlily (Victoria). An enlarged nasal horn without other compensation would make the nasals impossible to support, even with an ossified nasal septum, so the nasal horn has to shift posteriorly toward the frontal bone.

The skull exhibits enormous occipital condyles, as in other large nasal-horned elasmotheres and giant rhinos, indicating their dolichocephalic and heavy skulls. The longer skull yields great torque on the neck of elasmotheres. On the premise of retaining a huge horn, the elasmothere strategy followed two solutions: first, the nasal horn shifts posteriorly to become the frontal horn; second, the dolichocephalic skull becomes the brachycephalic. Both changes occurred in the skull of Elasmotherium, so its occipital condyles became smaller compared with the larger ones of Sinotherium, and its second premolars were lost, although Sinotherium retained them. Based on the skull, the nasal horn is known to enlarge gradually and shift posteriorly toward the frontal bone in derived elasmotheres; meanwhile, a smaller frontal horn develops and finally fuses with the nasal horn to form a huge frontal horn. This discovery explains a distinct transverse suture on the middle of the frontal horn boss of Elasmotherium, which was not understood in the past but is now determined as a remnant of the nasal and frontal horn bosses fusing to each other.

In the previous phylogenetic analyses, the position of S. lagrelii was not completely determined due to the lack of its skull. Given the new discovery, the cranial characters of S. lagrelii suggest that the monophyletic group including Sinotherium lagrelii, Elasmotherium sibericum, and E. caucasium would be appropriate, where S. lagrelii is the most basal and connects elasmotheres having a nasal horn but no a frontal horn with elasmotheres having a frontal horn but no nasal horn. This is consistent with the clade originating by the Late Miocene in China, and Elasmotherium being separate from Sinotherium at least since the Pliocene.

The area of distribution for Sinotherium in East Asia is similar to that of the steppe Hipparion fauna in the Late Miocene. The dolichocephalic skull, posteriorly inclined occipital surface, well-developed secondary folds, massive cement filling, and wrinkled enamel provide a means for the cheek teeth of Sinotherium to resist the abrasion of high-fiber diets so that it could graze on tough grasses. Sinotherium is a huge-sized rhinoceros with a weight up to 7 tonnes, much heavier than the largest modern African white rhino (3.2 to 3.6 tonnes), so if it lived by the river, it was easy to get stuck in the wet mud. More likely, S. lagrelii lived in an open, usually dry environmentwhere droughts frequently occurred in northern China. Early East Asian large elasmothere populations may have frequented steppe environments more than their more wet-adapted descendants in southern Russia. Because S. lagrelii is phylogenetically near the root of the frontal-horned elasmothere radiation, the reconstruction of steppe habitat for the species is an alternative against the proposal that the frontal-horned elasmotheres lived in wet habitat by rivers.

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Fig.1 Skull (V 18539) of Sinotherium lagrelii from the Linxia Basin (Image by DENG Tao)

Fig.2 A series of elasmotheres species that display an increase in skull size and development from a nasal horn to a frontal horn (illustrated by Chen Yu)

Fig.3 Habitat reconstruction of Sinotherium lagrelii in the Linxia Basin during the Late Miocene (illustrated by Chen Yu) |