| Location: Home > Research > Research Progress |

| Middle Pleistocene Teeth Adding New Data to the Discussion of Evolutionary Course in Asian Hominins |

|

Although a relatively large number of late Middle Pleistocene hominins have been found in East Asia, these fossils have not been consistently included in current debates about the origin of anatomically modern humans (AMHS), and little is known about their phylogenetic place in relation to contemporary hominins from Africa and Europe as well as to Upper Pleistocene hominins. Dr. LIU Wu, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his international collaborators present a detailed description and comparative analysis of four hominin teeth (I1, C1, P3 and P3) recovered from the late Middle Pleistocene cave site of Panxian Dadong, Guizhou of southwestern China, including two new teeth recovered in 1998-2000 and the reassessment of two teeth already described. The Panxian Dadong teeth combine archaic and derived features that align them with Middle and Upper Pleistocene fossils from East and West Asia and Europe, providing new data for the discussion about the evolutionary course of the Middle Pleistocene of Asia. Researchers reported online March 4 in Journal of Human Evolution (2013). For the past two decades, research and debates on modern human origins have focused on the emergence of AMHS around the world. Some recent fossil discoveries are interpreted as evidence that early modern humans appeared in East Africa by 160 ka or even earlier. In East Asia, because of the paucity of fossil discoveries and unreliable dating, it has long been argued that early AMHS did not appear until 50 ka. Recently, studies of new Upper Pleistocene hominin fossils from the Huanglong and Zhiren caves suggest that early AMHS may have been present in East Asia as early as 100 ka. In addition, a recent analysis of a Middle Pleistocene dental assemblage from Qesem Cave (Israel) leaves open the possibility that this non-African population may belong to early Homo sapiens. Thus, the phylogenetic and taxonomic assessments of the Middle Pleistocene lineages preceding the appearance of H. sapiens have become a crucial piece in the debate about the origins of modern humans. Panxian Dadong Cave (25°37’38’’N, 104°8’44’’E), is part of a large karst system that contains three connected stacked caves. In 1990, mammalian fossils and stone artifacts were first found in the cave. From 1992 to 2005, a collaborative international team of scientists headed by the IVPP conducted several seasons of excavations that yielded four hominin teeth and a lithic assemblage associated with an Ailuropoda-Stegodon fauna. Additional evidence of hominin activities in the cave consists of cut-marked and burnt bone. Faunal comparisons, Uranium-series dates of speleothems, and electron spin resonance dates on tooth enamel indicate that most of the excavated levels at Dadong were deposited between MIS 8 and MIS 6 (130-300 ka). Studies in the past twenty years confirm that Panxian Dadong contains an extensive record of late Middle Pleistocene human activities involving behavioral flexibility and unique adaptations to a mountainous environment. In order to examine East Asian dental evolutionary trends, researchers compared the Panxian Dadong teeth with a range of Middle and Upper Pleistocene hominins of Africa, Asia and Europe, particularly with several Chinese samples from early Middle Pleistocene, late Middle Pleistocene, Upper Pleistocene, and more recent prehistoric and modern human collections. The Panxian Dadong I1 and C1 present more archaic features than the P3 and the P3. The I1 is robust with a marked tuberculum dentale with finger-like extensions, although that feature is comparatively less complex than the morphologies of the Chinese mid-Middle Pleistocene fossils of H. erectus. The lower canine is robust but symmetrical in crown shape and it lacks any trace of a cingulum. The Panxian Dadong P3 displays more derived traits, falling within the range of variation of some European Middle Pleistocene hominins, Chinese Upper Pleistocene hominins, and particularly, West Asian early modern humans. Finally, the Panxian Dadong P3 combines some archaic and derived features that are commonly found in Chinese mid-Middle Pleistocene hominins, European Middle Pleistocene populations, and recent humans. “This mosaic of primitive and derived traits gives a glimpse of the high morphological diversity of the prehistoric populations that inhabited the vast geographical region of East Asia and raises the possibility of new evolutionary trends that have yet to be fully understood. Upper Pleistocene fossils from Africa and Europe have been generally classified as H. sapiens or Homo neanderthalensis. However, comparatively little is known about the evolution of human populations in Asia and the question remains how to relate late Middle Pleistocene and Upper Pleistocene fossils from Asia to either H. sapiens, Neanderthals, or to something else unique to Asia”, said Dr. LIU Wu, lead author of the study, “This problem is not exclusive to the Panxian Dadong sample, as it is a common problem when analyzing the Middle Pleistocene dental record from Africa and Asia”. “Although the Panxian Dadong teeth overlap in some morphological trends and in their dimensions with European Middle Pleistocene groups and the Neanderthals, they do not show any of the so-called typical Neanderthal traits nor any apomorphic feature that allow us to directly relate them to H. sapiens. However, our analysis reveals that the Panxian Dadong fossils are generally more derived than the Pleistocene fossils from North Africa, including the roughly contemporaneous C1 from Jebel Irhoud”, said coauthor Dr. María Martinón-Torres, Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), Burgos, Spain. “The phylogenetic position of the Middle Pleistocene fossils of Africa is less clear, and this is partially due to the scarcity of the fossil record for this period and region”, said coauthor Dr. Lynne A. Schepartz, School of Anatomical Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand Medical School, Johannesburg, South Africa, “Differences between the African and Asian Middle Pleistocene human assemblages may be pointing to different evolutionary trends for the populations of both continents and raise a number of unsolved questions about the evolutionary story of humans during the Middle Pleistocene. Current data and research have not yet confirmed or disproved whether late Middle Pleistocene and Upper Pleistocene hominins from Asia can fit within the variability of H. sapiens or Neanderthals, whether they are the result of the evolution in isolation of H. erectus, or whether they may even represent a fourth hominin lineage distinctive to Asia”. “We believe that the key to understanding the evolutionary fate of the Middle Pleistocene populations from Africa and Asia will derive from future fossil discoveries and more precise chronologies that help build a comparable fossil record and chronological framework between the continents. In the meantime, it is necessary to further investigate the polarity of morphological features present in the Middle Pleistocene groups and to identify Neanderthal and/or H. sapiens apomorphic traits”, said coauthor Dr. Erik Trinkaus, Department of Anthropology, Washington University, Saint Louis, “This study highlights the necessity of incorporating this new Asian evidence into the scientific debate about human evolution and the development of dental diversity in Homo lineages”. This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the US National Science Foundation, the Henry Luce Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Charles P. Taft Fund of the University of Cincinnati, the University of Cincinnati University Research Council, and the California State University, Stanislaus.

Fig.1. Geographic location and view of the entrance to Panxian Dadong. (Image by LIU Wu)

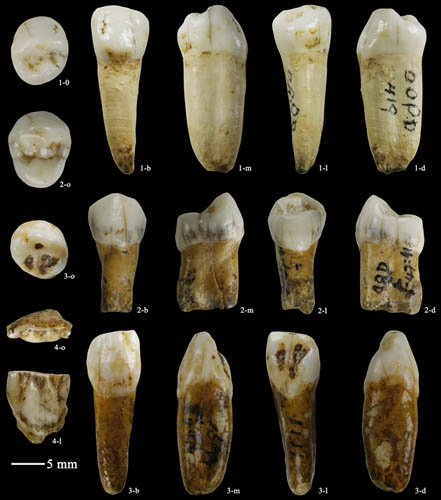

Fig.2 Four hominin teeth (I1, C1, P3 and P3) recovered from the late Middle Pleistocene cave site of Panxian Dadong. (Image by LIU Wu)

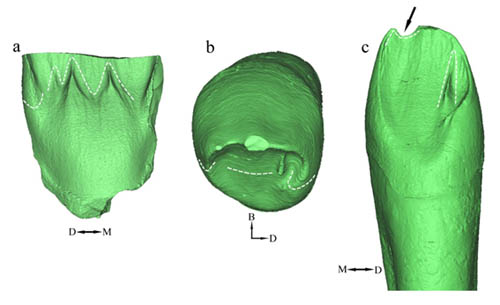

Fig.3. Views of enamel dentine junction (EDJ) of the lingual aspect of the I1 (a) and the occlusal and lingual aspect of the C1 (b and c) created from micro-CT scanning. (Image by LIU Wu) |