Very little was known about Mesozoic birds until nearly complete skeletons began to be discovered in the now famous Jehol Group deposits of northeastern China. The first few specimens to be found were partial skeletons, most preserving only the voids of the bones. Over the past two decades, new specimens have continued to be uncovered at an uprecedented rate. More recent published discoveries have typically been complete, including feathers, and benefited from recent advances in preparational techniques, thus providing a huge wealth of data regarding species diversity in northeastern China during the Early Cretaceous and the greatest wealth of data on Mesozoic birds anywhere in the world. Using this new data, a renewed look at the first few Jehol birds to be described reveals new information.

Paleornithologists of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, post-doctor Jingmai O’Connor, Director Zhou Zhonghe, and researcher Dr. Zhang Fucheng, reinvestigated Boluochia zhengi, one of the first birds described from the Jehol deposits. This taxon is very fragmentary, preserving clearly only the ankles and feet, however, this detailed study revealed that this species can now be assigned to the most diverse recognized group of enantiornithines, the Longipterygidae. Other members of this group (Longipteryx, Longirostravis, Shanweiniao and Rapaxavis) are all known from nearly complete specimens and preserve elongate rostra with teeth restricted to the tips of their jaws. This is interpreted as a trophic specialization that would have made food items available to members of this clade that were inaccessible to other birds, and may have contributed to their evolutionary success evident from their high species diversity. Although only a few fragments of the skull are preserved in the only known specimen of Boluochia, O’Connor, Zhou and Zhang were able to identify subtle clues that hint at the presence of an elongate rostrum in this taxon as well. These, however, could not be recognized until more complete specimens were discovered and available for comparison.

There are two lineages of longipterygids: those that are smaller with reduced hands (

Longirostravis,

Shanweiniao and

Rapaxavis), and a more basal lineage with large claws on the hands and large teeth, before only represented by

Longipteryx. Among longipterygids, O’Connor, Zhou and Zhang determined that the preserved morphology most closely aligns

Boluochia with

Longipteryx; unfortunately both taxa are from the younger Jiufotang Formation, and basal longipterygids (those with primitive morphologies such as claws on the hands such as

Longipteryx) remain unknown from the older Yixian formation that has produced the apparently more derived

Longirostravis and

Shanweiniao.

Boluochia and

Longipteryx share an unusual morphology of the foot, with metatarsals III and IV subequal in length, and a very large and robust pygostyle (the distal tail bone). However,

Boluochia can still be distinguished from

Longipteryx and the two remain separate species based on the outwards deflection of the outermost foot bone (distal end of metatarsal IV).

This project has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40121202), National 973 Project (TG20000077706).

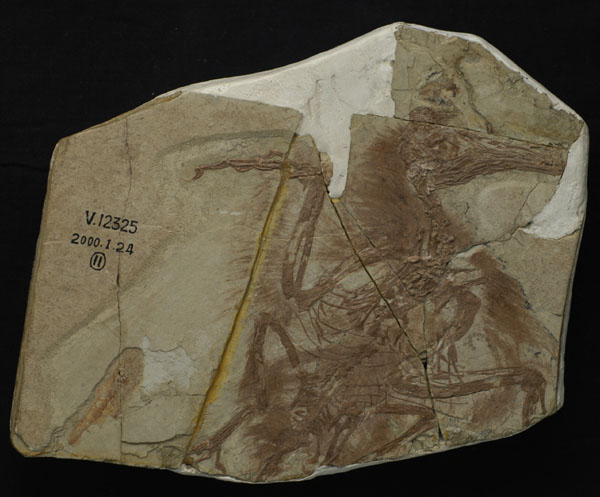

Figure 1. Photograph of the holotype of Longipteryx chaoyangensis (IVPP V12325). Scale bar represents 1 cm.(Image by O’Connor JK)