Quantitative analysis of Early Cretaceous Paraves shows a recent origin for the kinetic skulls behind the success of modern birds

A team of scientists led by Dr. Han HU from University of New England, Australia and Dr. Zhonghe ZHOU from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology(IVPP) of Chinese Academy of Sciences reported a new quantitative analysis of early Cretaceous paraves. This research was published in the latest issue of PNAS, in a paper entitled “Evolution of the vomer and its implications for cranial kinesis in Paraves”.

Birds are the only group of dinosaurs surviving through the end Cretaceous mass extinction. Its evolutionary success has been attributed to many biological adaptations, including cranial kinesis: a special ability to move the rostrum independent of the braincase, which is believed to be associated with feeding mechanisms. Cranial kinesis is made possible through the reduced lateral and flexible palatal structures, transferring force from the quadrate to elevate the upper bill. Thus, mobility of the palate is extremely important.

The closest dinosaurian relatives of birds are thought to have rigid skulls with no cranial kinesis. Although this feature has been the subject of great interest since first described, its origin and early evolution remains poorly understood in previous studies, largely due to the extremely rare preservation of the palate among early birds.

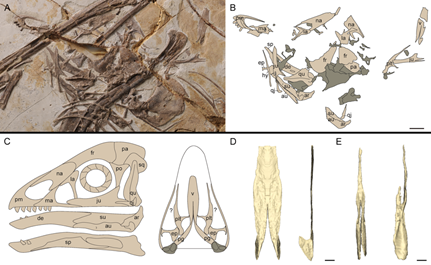

The researchers have recently made 3D reconstruction of the vomer (one of the palatal elements) of an Early Cretaceous bird Sapeornis and a troodontid Sinovenator, a non-avian dinosaur close to the dinosaur-bird transition. They provided new morphological information for the palate of these two early Paraves and enabled a preliminary reconstruction of the palate of Sapeornis, the first available for an Early Cretaceous bird.

Fig1. Photograph and camera lucida drawing of the skull of Sapeornis IVPP V19058; Cranial reconstructions of Sapeornis; 3D reconstructed vomers of Sapeornis IVPP V19058 and Sinovenator IVPP V12615 (Image by Dr. Han HU)

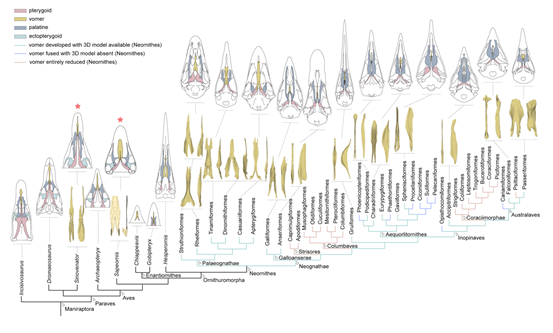

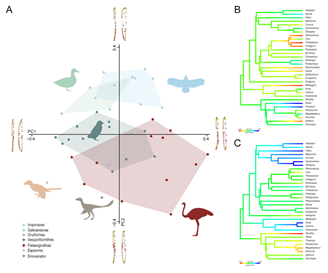

Based on the new 3D data from these two extinct lineages and representatives of modern birds, they conducted a comprehensive morphological study of the palate of birds, and a 3D geometric morphometric analysis focusing on the vomer.

Fig2. Palatal evolution from non-avian dinosaurs to crown birds (Image by Dr. Han HU)

(Image by Dr. Han HU)

The results indicate that the Palaeognathae retain the plesiomorphic morphology of the palate inherited from non-avian dinosaurs. In contrast, the neognathous palate is much more modified with the vomer played a prominent role in this evolutionary transition. Basal birds, like palaeognaths, had limited cranial kinesis, a conclusion also supported by the identification of an ectopterygoid in Sapeornis. This suggests that the remarkably flexible avian skull is likely to be an innovation of the Neognathae, evolved after its divergence from the Palaeognathae in the Late Cretaceous. The greater efficiency and evolutionary plasticity of the neognathous feeding mechanism afforded by the evolution of cranial kinesis may have increased the adaptability of this clade, allowing them to diversify into a wider array of ecological niches compared to the palaeognaths, and thus ultimately be at least partially responsible for the current success of the neognathous radiation.

Fig3. Principal components analysis result of vomer shape in Paraves (PC1 & PC2) (Image by Dr. Han HU)

Download attachments: