Ancient Chinese Skull Has Neandertal-like Inner Ear

A closer look based on micro-CT scans at a 100,000-year-old human skull that was recovered 35 years ago in China revealed that it had an inner ear formation that was thought only to have occurred in Neanderthals. In comparison, none of the three other archaic human skulls analyzed from different parts of China had this type of inner ear. Researchers from Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis of USA, and Université de Bordeaux in Talence of France, detailed their findings July 07 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study therefore raises questions regarding possible biological correlates of labyrinthine morphology, distinctive Neandertal features, and the nature of late archaic human variation across Eurasia.

The skull that was used in the study, known as Xujiayao 15, was found along with teeth and bone fragments in the Xujiayao site in the Nihewan Basin of northern China, all of which seemed to have characteristics typical of an early non-Neandertal form of late archaic humans.

Although modern humans are the only living members of the human family tree, a number of other human lineages once lived alongside the ancestors of modern humans. These so-called archaic humans included Neanderthals, the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, who lived in Eurasia roughly between 200,000 and 30,000 years ago.

The inner ear, also known as the labyrinth, is located within the skull's temporal bone. It contains the cochlea, which converts sound waves into electrical signals that are transmitted via nerves to the brain, and the semicircular canals, which help people keep their balance when they change their spatial orientations, such as when running, bending over or turning the head from side-to-side. These semicircular canals are often well-preserved in mammal skull fossils, the researchers said.

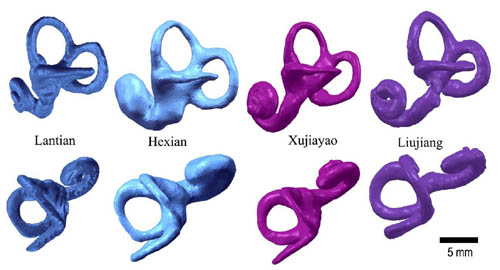

Since the mid-1990s, when early CT-scan research confirmed its existence, the presence of a particular arrangement of the semicircular canals in the temporal labyrinth has been considered enough to securely identify fossilized skull fragments as being from a Neandertal. This pattern is present in almost all of the known Neandertal labyrinths. It has been widely used as a marker to set them apart from both earlier and modern humans.

The assessment of the paleobiology and morphological affinities of the Neandertals and other Late Pleistocene archaic humans is central to resolving issues regarding the emergence and establishment of modern human morphology and diversity.

While it's tempting to use the findings as evidence of population contact between central and western Eurasian Neanderthals and eastern archaic humans in China, broader implications of the Xujiayao discovery remain unclear, said lead author Dr. WU Xiujie of the IVPP.

"The study of human evolution has always been messy, and these findings just make it all the messier," said study coauthor Dr. Erik Trinkaus, Washington University in St. Louis, "It shows that human populations in the real world don't act in nice simple patterns. This study shows that you can't rely on one anatomical feature or one piece of DNA as the basis for sweeping assumptions about the migrations of hominid species from one place to another."

This work has been supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Fig.1 The Xujiayao 15, late archaic human temporal bone with the extracted temporal labyrinth superimposed on a view of the Xujiayao site in the Nihewan Basin of northern China. (Image by WU Xiujie)

Fig.2 Reconstructed temporal labyrinths of East Asian Pleistocene humans from Lantian 1 (reversed), Hexian 1, Xujiayao 15, and Liujiang 1 (reversed), in lateral (Upper) and superior (Lower) views. (Image by WU Xiujie)

Download attachments: