Oldest Pterodactyloid Species Discovered in Northwest China

The pterodactyloid is a group of short-tailed pterosaurs with elongate-metacarpus that appeared in the middle Late Jurassic and quickly became the most diverse pterosaur group, replacing all others. A Sino-American expedition team lead by Dr. XU Xing, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Dr. James M. Clark of The George Washington University, discovered a new pterosaur species, Kryptodrakon progenitor, gen. et sp. nov., from the Shishugou Formation of northwest China. This finding represents the earliest and most primitive pterodactyloid pterosaur and extends the fossil record of pterodactyloids by at least five million years to the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary about 163 million years ago, according a paper published April 24 online in the journal of Current Biology.

The creature's name is a reference to the film "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon," which was filmed near where the fossil was discovered. "Krypto" means hidden and "drakon" means serpent in Greek. "Progenitor" means ancestral or first-born in Latin and refers to the creature's status as the earliest pterodactyloid.

The specimen was collected from a mudstone in the alluvial facies, 35 m below the T-1 marker tuff of the lower part of the Shishugou Formation at Wucaiwan, Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China.

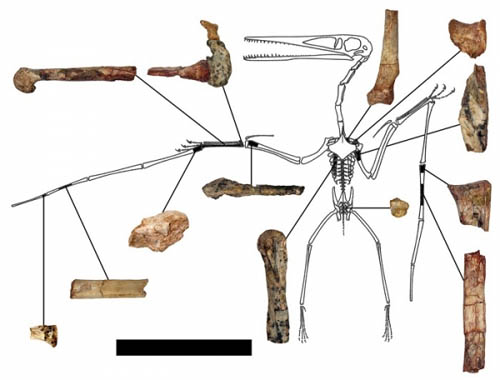

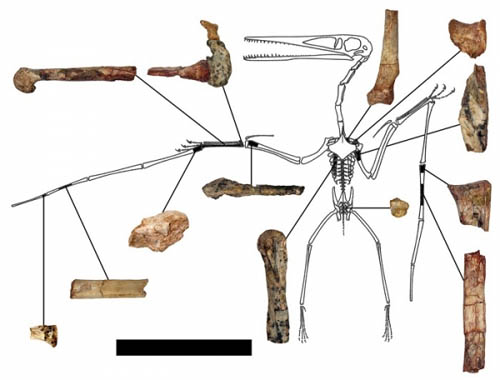

The preserved remains of Kryptodrakon progenitor include a partial sacrum, ventral ramus of the left coracoid, anterior end of the right scapula, proximal end and shaft of the left humerus, distal end of the right radius, right distal syncarpal, right preaxial carpal, right wing metacarpal, proximal end of the right first wing phalanx, proximal end and shaft of the left second wing phalanx, shaft of the right third wing phalanx, proximal end of the right fourth wing phalanx, and a number of indeterminate fragments. This individual is considered an osteological adult based upon the fusion of the sacrum, scapulocoracoid, and distal syncarpal. It is a small pterodactyloid with a wingspan estimate of 1.47 m.

The sudden appearance and many diagnostic features of the pterodactyloid pterosaurs have been suggested to be the result of the group originating in terrestrial environments where the pterosaur fossil record has traditionally been poor, but this has not been supported by previous analyses or early pterodactyloid discoveries.

The result of phylogenetic analysis confirms this species as the basal-most pterodactyloid and reconstructs a terrestrial origin and predominantly terrestrial history for the Pterodactyloidea. Phylogenetic comparative methods support this reconstruction by means of a significant correlation between wing shape and environment also found in modern flying vertebrates, indicating that pterosaurs were adapted to the environments in which they were preserved.

"Our finding contends that the pterodactyloids hailed from the land, originating, living, and evolving on terrestrial environments - rather than marine environments where other specimens have been found”, said study coauthor Dr. XU Xing of the IVPP.

"The physical demands of flight are extreme and vary with environment. At the origin of the Pterodactyloidea, the greatest change in the flight apparatus was the change in the metacarpus, which transitions from being the shortest and least variable in length of the major wing elements in the non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs to the longest and most variable in length within the pterodactyloid pterosaurs. The elongation of the metacarpus is the diagnostic feature of the Pterodactyloidea, but the increased variation in length producing this elongation is likely a key innovation allowing new and more varied wing shapes for the Pterodactyloidea to radiate into new and more varied environments”, said lead author Dr. Brian Andres, a paleontologist at University of South Florida.

The research was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Science Foundation Division of Earth Sciences of the USA, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Fig.1 Preserved remains of Kryptodrakon progenitor (IVPP V18184). The skeletal outline is Pterodactylus antiquus reprinted with permission from Peter Wellnhofer with preserved elements filled in black. Scale bar is 50 mm. (Image by Brian Andres)

Fig.2 Life restoration of Kryptodrakon progenitor and the pterosaur fauna from the Shishugou Formation of Xinjiang, China. Kryptodrakon is depicted on the left escaping from Sericipterus wucaiwanensis on the right. The centre pterosaur represents two indeterminate wing phalanx fragments found in the same formation. (Image By John Conway)