Fossil Fishes from China Provide First Evidence of Dermal Pelvic Girdles in Osteichthyans

The fossil record shows that the pectoral girdles of early osteichthyans retained part of the primitive gnathostome pectoral girdle condition with spines and/or other dermal components. However, very little is known about the condition of the pelvic girdle in the earliest osteichthyans. Dr. ZHU Min, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team reported the first discovery of spine-bearing dermal pelvic girdles in early osteichthyans, based on a new articulated specimen of Guiyu oneiros from the Late Ludlow (Silurian) Kuanti Formation, Yunnan, as well as a re-examination of the previously described holotype. They also observed disarticulated pelvic girdles of Psarolepis romeri from the Lochkovian (Early Devonian) Xitun Formation, Yunnan, resemble the previously reported pectoral girdles in having integrated dermal and endoskeletal components with polybasal fin articulation.

This new finding, published in the April 3 issue of the journal of PLoS ONE, reveals hitherto unknown similarity in pectoral and pelvic girdles among early osteichthyans, and provides critical information for studying the evolution of pelvic girdles in osteichthyans and other gnathostomes.

The pectoral and pelvic girdles support paired fins and limbs, and have transformed significantly in the diversification of gnathostomes or jawed vertebrates (including osteichthyans, chondrichthyans, acanthodians and placoderms). For instance, changes in the pectoral and pelvic girdles accompanied the transition of fins to limbs as some osteichthyans (a clade that contains the vast majority of vertebrates - bony fishes and tetrapods) ventured from aquatic to terrestrial environments.

The pectoral girdles of gnathostomes primitively combine dermal and endoskeletal elements, as in jawless osteostracans even though the osteostracan pectoral girdles are fused to the cranium. However, the primitive condition for pelvic girdles is less clear, resulting from the scarcity of articulated early gnathostome postcrania and the absence of girdle-supported pelvic fins in all known jawless fishes.

Living osteichthyans, like chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fishes), have exclusively endoskeletal pelvic girdles, while dermal pelvic girdle components (plates and/or spines) have so far been found only in some extinct placoderms and acanthodians. Consequently, whether the pectoral and pelvic girdles are primitively similar in osteichthyans cannot be adequately evaluated, and phylogeny-based inferences regarding the primitive pelvic girdle condition in osteichthyans cannot be tested against available fossil evidence, or it is difficult to explore how and when the living osteichthyans may have acquired their exclusively endoskeletal pelvic girdles.

“Although previous studies of Guiyu and Psarolepis have advanced our understanding of early osteichthyan morphologies, no pelvic girdle components were identified or described at the time, and the primitive condition of pelvic girdles in osteichthyans remained unknown. The situation started to change when a new articulated specimen of Guiyu oneiros was collected in 2010 from the Late Ludlow (Silurian) Kuanti Formation, Yunnan, China. After observations of this new specimen, re-examination of the holotype of Guiyu oneiros, and studies of previously unidentified disarticulated specimens of Psarolepis, we finally discerned pelvic girdles with substantial dermal components (plates and spines) in these two early bony fishes”, said ZHU Min, lead author and project designer.

The pelvic girdles of Guiyu oneiros and Psarolepis romeri are striking in their similarity to the pectoral girdles of these taxa and to the pelvic girdles of placoderms. This challenges existing hypotheses regarding early osteichthyan pelvic evolution based on the putative absence of dermal components and the dissimilarity of the pectoral and pelvic anatomy.

Previously, osteichthyans were known to have very different pectoral and pelvic girdles (the former with endoskeletal and dermal components while the latter being exclusively endoskeletal). The new material, coupled with previously reported pectoral girdle findings, reveals hitherto unknown similarity in pectoral and pelvic girdles in early osteichthyans, both featuring a massive endoskeletal girdle integrated with dermal plates, spines, and polybasal fin articulation.

“As the first evidence for the presence of dermal pelvic girdles in osteichthyans, the pelvic girdles in Guiyu and Psarolepis reveal an unexpected morphology that stands in stark contrast to the inferences from published phylogenetic analyses, and appear to resemble those of placoderms rather than either the acanthodians or, indeed, any other previously known osteichthyans”, said Xiaobo Yu, the study coauthor and project designer, professor of Department of Biological Sciences, Kean University, New Jersey, USA., “The data presented here provide new morphological information for more focused future studies of these and other phylogenetically controversial Silurian–Devonian osteichthyan forms.”

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Major Basic Research Projects of MST of China, the National Nature Science Foundation of China, and the CAS/SAFEA International Partnership Program for Creative Research Teams.

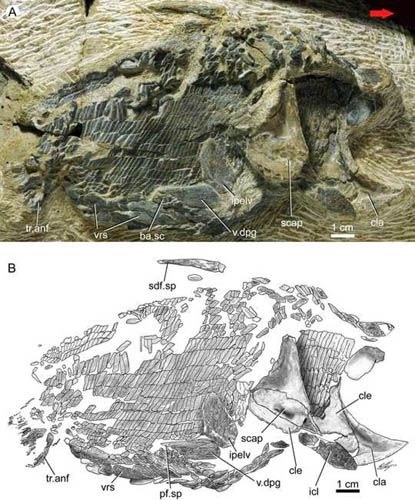

Fig.1. New articulated specimen (A) and interpretative drawing (B) of Guiyu oneiros (IVPP V17914, lateral view) from the Kuanti Formation (Late Ludlow, Silurian), Qujing, Yunnan, showing a right dermal pelvic girdle in near-natural position. The girdle is an oblong bone 17 mm in length (excluding spine) and 7 mm in width with a sharp posterolateral spine. Red arrow points to the anterior end of the fish. (Images by ZHU Min)

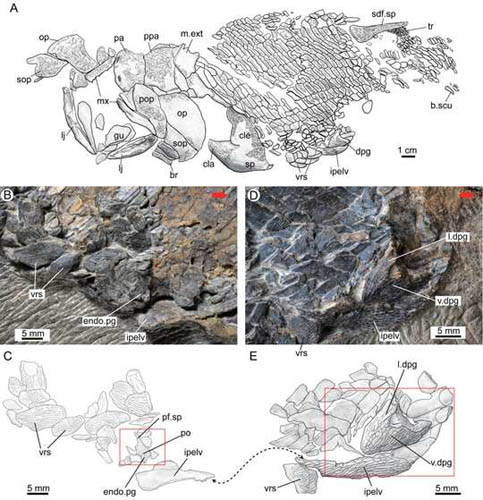

Fig.2: Holotype of Guiyu oneiros (IVPP V15541). A. Interpretative drawing of the part to show the position of the newly identified left pelvic girdle with dermal and endoskeletal components. B–C. Close-up of the counterpart to show the endoskeletal pelvic girdle in internal view (B) and interpretative drawing (C). D–E. Close-up of the part to show the dermal pelvic girdle in lateral view (D) and interpretative drawing (E). Red arrows point to the anterior end of the fish. (Images by ZHU Min)

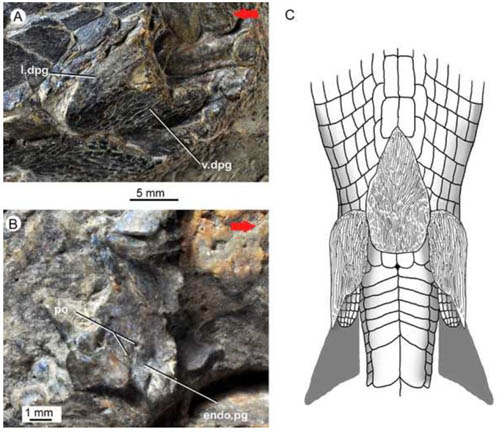

Figure 3. Guiyu oneiros. A. Close-up of the holotype (in part) to show the dermal pelvic girdle in lateral view. B. Close-up of the holotype (in counterpart) to show the endoskeletal pelvic girdle in internal view. C. Tentative life restoration in ventral view to show the paired pelvic girdles and unpaired interpelvic plate. Red arrows point to the anterior end of the fish. (Images by ZHU Min and Brian Choo)

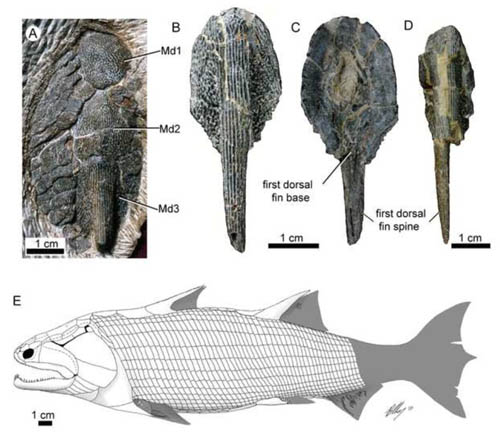

Figure 4. Guiyu oneiros. A. Close-up of the three median dorsal plates (Md1-Md3) of the holotype IVPP V15541. B–C. A disarticulated third median dorsal plate (Md3) bearing the first dorsal fin spine in external (B) and internal (C) views, IVPP V17914.2. D. A disarticulated third median dorsal plate (Md3) in external view, IVPP V17914.3. E. Revised restoration of Guiyu oneiros in lateral view. (Images by ZHU Min)

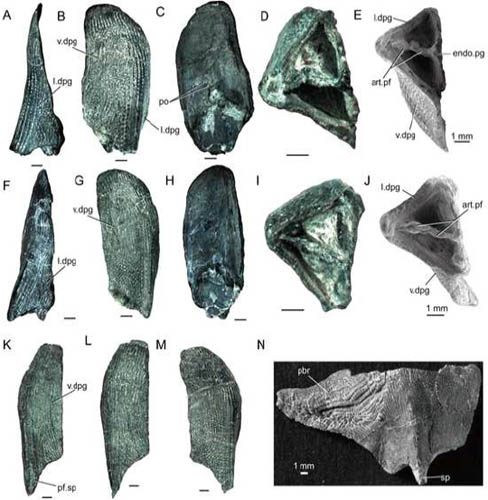

Fig.5: Psarolepis romeri, from the Lower Devonian Xitun Formation (Lochkovian) of Qujing, Yunnan. A–E. Disarticulated left pelvic girdle in lateral (A), ventral (B), internal (C) and posterior (D–E) views, IVPP V17913.2. F–J. Disarticulated left pelvic girdle in lateral (F), ventral (G), internal (H) and posterior (I–J) views, V17913.1. K. Disarticulated right pelvic girdle in ventral view, IVPP V17913.5. L. Disarticulated right pelvic girdle in ventral view, IVPP V17913.4. M. Disarticulated left pelvic girdle in ventral view, IVPP V17913.3. N. Disarticulated left pectoral girdle in ventrolateral view, IVPP V15544.1. E and J are SEM photos. All scale bars equal 1 mm. (Images by ZHU Min)

Download attachments: