The identification of traumatic lesions in human fossils is of special interest because of the underlying behaviors that are involved: accidental or intentional wounding, potential interpersonal violence, and also the social support needed for the care and recovery of impaired individuals. Aside from the Neandertals, secure evidence of healed traumatic lesions is very rare among Pleistocene human remains.

The research of the late Middle Pleistocene archaic human cranium from Maba, south China, brings to the new evidence that interhuman aggression and healed blunt force trauma as early as 129,000 years ago in East Asian.

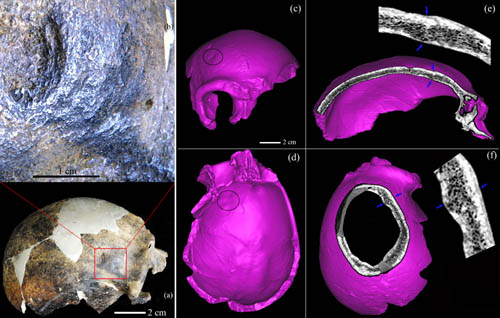

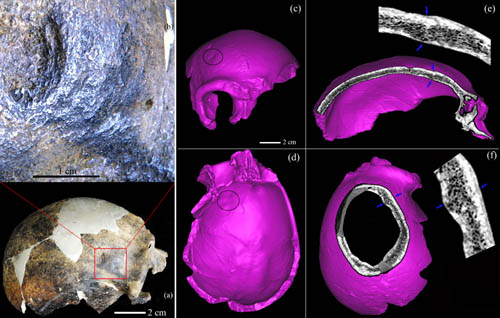

The report published on Monday, 21 November 2011, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) documents a lunate lesion on the right frontal squamous exocranially concave and ridged lesion with endocranial protrusion. Differential diagnosis indicates that it resulted from localized blunt force trauma, due to an accident or, more probably, interhuman aggression.

The area of the depressed portion of the vault lesion is 14.0 mm in length and 1.5 mm in its deepest point below the frontal external contour. The center of the depression is rough. Several concentric waves within it created rounded edges, none of which is a complete circle. When the lesion is enlarged, healing of the bone can be seen to have taken place surrounding the area of the depressed area. The trauma is very similar to what is observed today when someone is struck forcibly with stones or staves. Its remodeled, healed condition also indicates the survival of a serious brain injury. It is not possible to assess whether the incident was accidental or intentional, or whether it resulted from a short-term disagreement, or premeditated aggression.

Neurocranial abnormalities had been found in Chinese human fossils; however, when evaluated by paleopathological and forensic diagnostic standards, none represents definitely traumatic lesions caused by interpersonal violence. The depressions or damages on the Zhoukoudian H. erectus crania were suspected to hominid agency, but they could be more likely made by geological-crushing from the weight of overlying sediment or carnivores. The lesion on the supraorbital of the Lantian (Gongwangling) calvarium, initially thought to be a healed antemortem trauma, were later ascribed to postmortem taphonomic alterations of the bone. The Middle Pleistocene partial cranium from Hulu Cave, Tangshan, Nanjing, exhibits an ecdocranial healed lesion that was caused by either trauma or burning.

Maba cranium was discovered in 1958, in a karst cave at Lion Rock, Maba town, Qujiang district, Shaoguan city, Guangdong province. The Maba cranium and a large quantity of mammal fossils were found in a deep and narrow crevice inside the cave. Maba has a thick, prominent and projecting supraorbital torus that arches over the circular profile orbits. The nasal bones are narrow, pinched and strongly projecting. Since its unique morphology in the middle stage of Early Homo Sapiens from mainland northern eastern Asia, Maba has been described extensively from a comparative morphological perspective. Although lots of researchers studied the Maba partial cranium, no one pay more attention and analysis the special lesion. Using a high-resolution industrial CT scanner and stereomicroscopy, Dr Xiu-jie WU and her co-author suggested that the Maba individual survived from serious injury and post-traumatic disabilities, and that it obviously did not kill the person. Maba would have needed social support and help in terms of care and feeding to recover from this injury long before death.

The Maba 1 lesion joins a series of other craniofacial traumatic lesions of Pleistocene humans which provide evidence of both apparently elevated levels of risk to injury and the ability to survive both major and minor conditions.

This research was mainly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

(Link:

www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1117113108)

Figure 1. Right superior view of the Maba cranium shows the position and detail of the depressed lesion (Image by IVPP)

Figure 2. The living scene of the Maba human (Image by IVPP)