| Location: Home > News > Events |

| Global Times:From fish to human: ancient fossil unearthed in China sheds light on evolution |

|

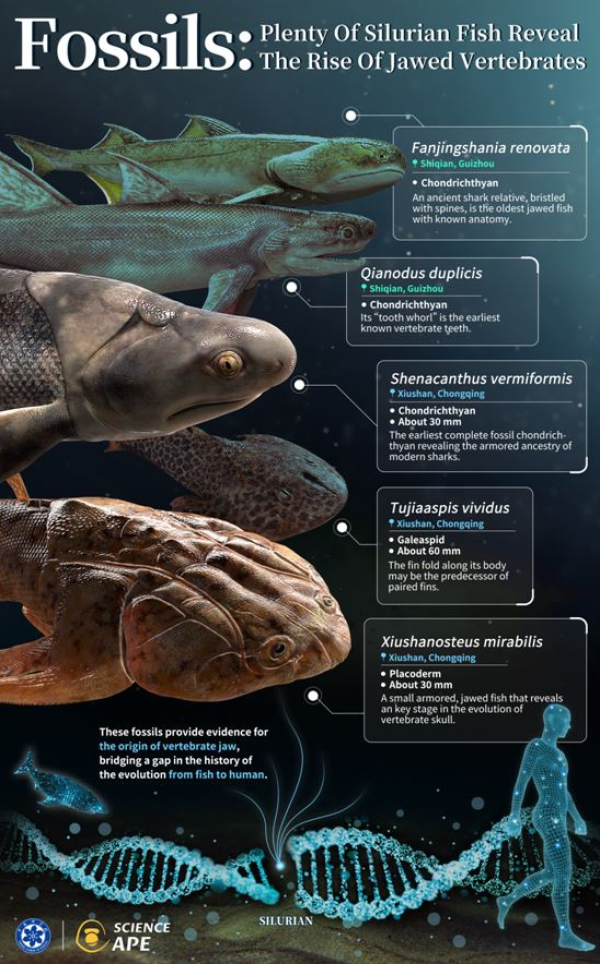

A collection of well-preserved fish fossils were unearthed in two newly discovered fossil beds from the early Silurian Period - around 439 to 436 million years ago - in Southwest China's Chongqing Municipality and Guizhou Province. Scientists said it could provide insights into the rise and diversification of jawed animals, including humans, rewriting the evolutionary story of "from fish to human." The research team led by Zhu Min, from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), adopted new technologies and methodologies including high-precision CT (Computed Tomography), big data analysis and hydrodynamic analogy. Using these methods, they presented the world for the first time the oldest teeth from any jawed vertebrate, and what used to be completely unknown - the body structure and anatomy of the oldest jawed vertebrate, the Global Times learned from the research team on Wednesday. Their findings provide solid evidence for scientific issues such as "how fish evolved into humans" and renew humanity's knowledge of the history of the evolution of jawed vertebrates, according to the institute. Jawed vertebrates make up more than 99.8 percent of modern vertebrates, including humans. These jawed vertebrates, also known as gnathostomes, are thought to have originated around 450 million years ago. The emergence and rise of jawed vertebrates is believed to mark a key innovation "from fish to humans," and many vital organs and body structures of humans could date back to the early evolutionary history of jawed vertebrates. However, the scarcity of fossil evidence from this era makes it hard to reconstruct the early evolutionary history of jawed vertebrates. Previously, the earliest articulated jawed fish fossils identified to date were from around 425 million years ago. Hence, there has been a huge gap in the fossil record of the early jawed vertebrates, spanning at least 30 million years from the Late Ordovician through most of the Silurian.

To fill in this gap, which has been dubbed "a persisting major gap in our paleontological record" by the famous paleontologist Alfred Romer, Zhu's team spent the past decade visiting more than 200 Silurian rock beds in China where there might be fish fossils. They eventually discovered the Chongqing Biota, which dates back 436 million years - the world's only early Silurian Lagerst?tte. It preserves complete, "head-to-tail" jawed fishes, providing a peerless chance to peek into the proliferating "dawn of fishes," according to the institute. Their finds included placoderms, an extinct group of armored prehistoric fish, which were the earliest known jawed vertebrates and chondrichthyans, a group of cartilaginous fish such as sharks and rays. The dominant species was a roughly 3 cm long placoderm given the name Xiushanosteus mirabilis. This fish displays a combination of features from major placoderm subgroups that sheds light on the evolution of the skulls of living jawed vertebrates. A chondrichthyan named Shenacanthus vermiformis has a body shape similar to other cartilaginous fish, but it is found to have armor plates more commonly associated with placoderms. These discoveries reveal previously unknown diversification in this period. Zhu told the Global Times on Wednesday that "the unearthing work continues to yield remarkable materials. The Chongqing Lagerst?tte, like the Chengjiang and Jehol biotas, will become a world-famous paleontological heritage site and provide key evidence for how the extraordinary diversity of the jawed vertebrates we see today rose." "It's really an awesome, game-changing set of fossil discoveries. It rewrites almost everything we know about the early history of jawed animal evolution," said John Long, former president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology [2014-2016], who teaches at Flinders University, Australia. The Guizhou depository dates back some 439 million years and contains sequences of sedimentary layers from the distant Silurian Period [from around 445 to 420 million years ago]. It has produced spectacular fossil finds, including isolated teeth identified as belonging to a new species named Qianodus duplicis of primitive jawed vertebrates. Called after the ancient name of Guizhou, Qianodus possessed peculiar spiral-like dental elements carrying multiple generations of teeth that were added throughout the life of the animal. The discovery of Qianodus provides tangible proof for the existence of toothed vertebrates and shark-like dentition patterning 14 million years earlier than previously thought. Silurian vertebrate localities in Guizhou, and those elsewhere outside China, have been of great interest to paleontologists studying the origins and early diversification of vertebrates. "What puzzled the researchers was the absence of teeth or other recognizable dental elements," said Qiang Li, one of the authors of the study and a lead scientist of the early vertebrates research group at Qujing Normal University. "Now Qianodus provides us with the first tangible evidence for teeth from this critical early period of vertebrate evolution." The findings will be published in the journal Nature on Wednesday in four articles including a cover story.

|