| Location: Home > News > Events |

| National Geographic:Ancient teeth hint at mysterious human relative |

|

FOUR TEETH FOUND in a cave in the Tongzi county of southern China have scientists scratching their heads. In 1972 and 1983, researchers extracted the roughly 200,000-year-old teeth from the silty sediments of the Yanhui cave floor, initially labeling them as Homo erectus, the upright-walking hominins thought to be the first to leave Africa. Later analysis suggested they didn't quite fit with Homo erectus, but that's where the story paused for nearly two decades. Now, a study published in the Journal of Human Evolution takes a fresh look at these ancient teeth, using modern methods to examine the curious remains. The new analysis excludes the possibility that the teeth could come from Homo erectus or the more advanced Neanderthals, but the elusive owner remains unknown. “It’s strange. We don’t know where to put it,” says study author Song Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. The four teeth join a growing number of finds in China that don't tidily fit onto the known branches of the human evolutionary tree, hinting that there's more to the story of human history in this region. “We always think of Africa as the 'cradle of humankind,'” says study author María Martinón-Torres, director of Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana in Spain. “I would say it’s a cradle of probably one of the human kinds, which is Homo sapiens.” But many human species once walked the Earth, and what is going on in Asia, she says, is likely “crucial to understanding the whole picture.” Dental sleuthing Humankind's story has grown increasingly complex in recent years, with ever more chapters and characters added to the mix. Migration of Homo erectus-like hominins started some two million years ago, as evidenced by stunningly old tools recently recovered from central China. Over the next hundreds of thousands of years, other groups continued to make the trek and scatter their remains across the world. As these early adventurers made their way into foreign lands and climates, they diversified into an array of populations. Neanderthal forerunners spread through Europe and the Middle East. Other hominins headed for southeast Asia, giving rise to the short-statured Homo floresiensis in present-day Indonesia and the stone tool-users of the Philippines. So where do the Tongzi teeth belong? “We have only a very small number of these materials,” Xing says with caution. “But now we can put some imagination into it.”

The latest study tackles the structures and patterns of the Tongzi teeth, detailing their surfaces and innards using a method known as micro-computed tomography. The team compared their data to both ancient and more modern tooth samples from Africa, East Asia, West Asia, and Europe. They found that the Tongzi teeth are a patchwork of ancient and modern traits. In particular, the tissue beneath the enamel, known as dentine, lacks the telltale crinkles found in teeth from Homo erectus. Many of the teeth instead have a notable simplicity thought to be similar to later Homo species like the Neanderthals. But taken as a whole, the tooth features just don't fit into either category. One tantalizing possibility is that the teeth could come from the enigmatic hominin group known as the Denisovans, which is thought to have split from the Neanderthals at least 400,000 years ago. Known from just three molars, a pinky, and a skull fragment recovered from a single Siberian cave, the group is best recognized by its genetic fingerprints. Hints of Denisovan DNA still linger in modern people across Asia, in particular, populations in Oceania.

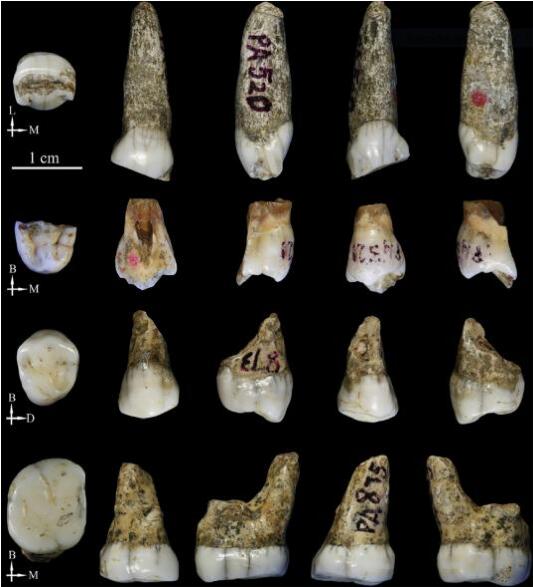

A composite picture shows multiple views of the four teeth, which display a mosaic of both ancient and more modern features. PHOTOGRAPH BY S. XING One big issue is that the Tongzi and Denisovan teeth can't be directly compared, because they aren't from the same position in the mouth, says paleoanthropologist Bence Viola of the University of Toronto, who revealed the Denisovan skull fragment last week at an anthropology meeting in Ohio. While the teeth appear fairly large—a notable feature of the Denisovans—the limited physical remains make it tough to say anything more definitive without genetic evidence. And preserving the delicate DNA structure is challenging in the heat and humidity of southern China. “This is clearly a distinct population. Whether they’re the same population as Denisovans is not completely clear,” says Viola, who is also part of the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Shara Bailey, a dental paleoanthropologist at New York University, is skeptical of Denisovan affinity for this particular sample. “I am sure that there is Denisovan material out there,” she says. “The thing is, is that until we have good comparative cranial and mandibular material, it’s just a guessing game.” The ancient parade Another possibility is that the new Chinese fossils come from some hybrid lineage. Multiple groups likely crossed paths during this time period, and whenever hominins mixed, they seemed to interbreed. Just last year, scientists identified a fragment of bone from an ancient teenager who had a Neanderthal mom and Denisovan dad. When Denisovan ancestors ventured into Asia, for example, they could have met the population already there, Homo erectus, and interbred to create a group that produced the Tongzi teeth, Viola says. A mystery in Denisovan DNA could prop up this suggestion: Past genetic analysis suggested that a small percent of Denisovan DNA came from an unknown but super-ancient hominin. But without DNA from the Tongzi fossils, scientists are still just guessing. For now, the study represents an important step in unraveling the full extent of the human story. While researchers have long studied these Chinese fossils, the results were often not translated into English, limiting its integration into the broader picture, notes Chris Stringer of London's Natural History Museum. What's more, Bailey says, access to the Chinese fossils has been limited, which constrained scientific understanding. But now that's changing, and the more scientists look, the more complexity they seem to find. A variety of other Chinese fossils dating to between 360,000 and 100,000 years old also don't fit into neat boxes. These include teeth with surprisingly advanced features from Panxian Dadong in southern China and robust chompers found at the Xujiayao site of northern China. Then there's the skull fragments. One particularly intriguing sample is a remarkably complete skull from Harbin, China. While it's not yet scientifically described, its features portray a face more ancient than a Neanderthal's, so it could belong to a group that branched from this line early on, Stringer notes. “I think there's something separate in China—even without DNA I think we can say that,” Stringer says. But for more specifics, scientists will need more evidence. As Kristin Krueger of Loyola University says via email, the study “showcases a cultural shift in paleoanthropology—one that recognizes that our story is much more intricate and complex than we realized—and that our story is always changing.” (By ) |