| Location: Home > News > Events |

| Xinhua:Ancient grass grazers survive to be today's elephants |

|

We may not see elephants roaming the prairies or forests today, if their distant ancestors had not learned to graze on grass about 16 million years ago. Their active adaption to the environment helped the species to survive.

Life restoration of G. steinheimense. Drawing provided by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology By Quan Xiaoshu, Qu Ting We may not see elephants roaming the prairies or forests today, if their distant ancestors had not learned to graze on grass about 16 million years ago. G. steinheimense, which belonged to the Gomphotherium family, a type of ancient elephant, began to feed entirely on grass as its environment changed, according to a paper published on Scientific Reports online journal by the Nature Publishing Group. Wu Yan, a researcher at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and colleagues drew the inference by comparing the fossil molars of two different types of Gomphotherium, which were found in the Miocene sediment in the Junggar Basin, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

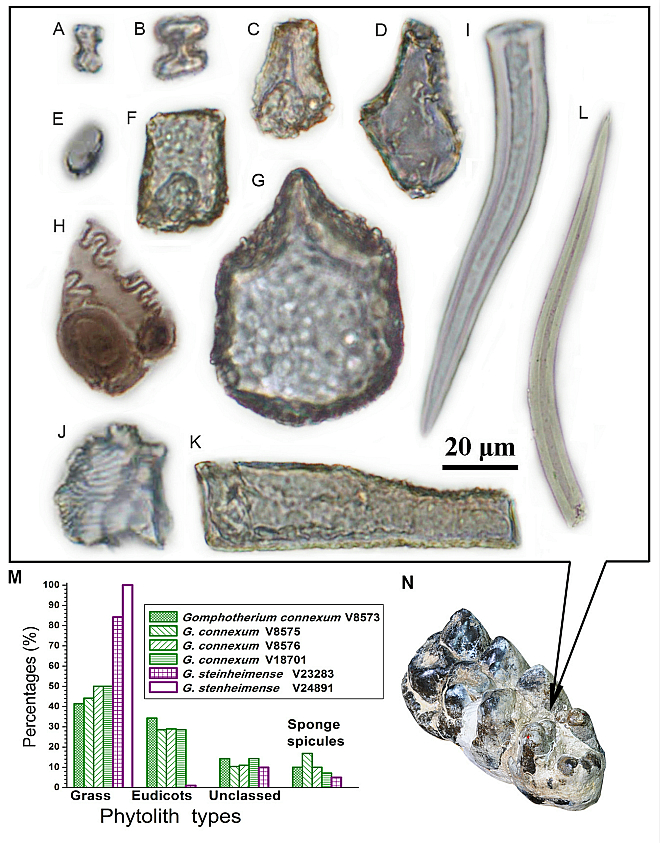

Wu Yan at work. Photo provided by Wu Yan "We examined the phytoliths sealed within their dental calculus, which showed an extensive dietary record," said Wu, first author of the paper. Phytoliths, "plant stone" in Greek, are rigid, microscopic structures made of silica, found in some plant tissues and persisting after the decay of the plant. In the dental calculus of G. steinheimense, grass phytoliths amounted to 85 percent and no leaf phytoliths were found, which indicated that G. steinheimense were grazers rather than browsers.

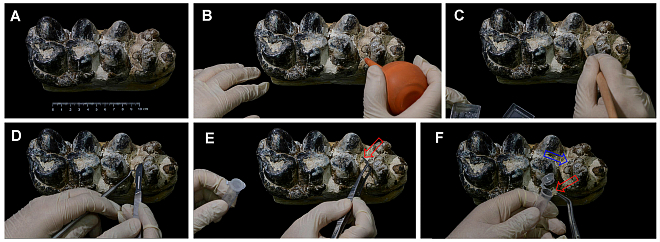

Samples of dental calculus taken from the fossil. Photo provided by Wu Yan

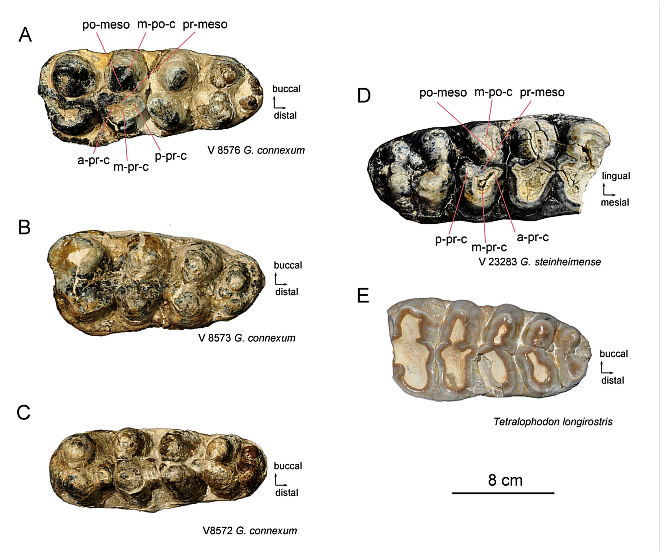

Comparison of phytoliths within dental calculus of two different types of ancient elephants. Photo provided by Wu Yan By contrast, the researchers found only 40 percent to 50 percent of grass phytoliths in the dental calculus of G. connexum, another type of Gomphotherium, as well as consistent evidence of leaf remains, ranging from 28 percent to 34 percent among four of their molars. "The leaves were from eudicots, which produced considerably fewer phytoliths on average than grasses. It suggested that eudicot leaves were probably a staple for G. connexum, which was either a mixed-feeder of both grass and foliage, or even primarily a browser," Wu said. Their different diets shaped different evolutionary destinies. Pollen records show that the climate became drier between the Middle and Late Miocene, which led to the evolution of drought-tolerant plants and expansion of grasslands in Central Asia. But few of the ancient elephants wandering the expanding prairie were aware of what was happening. Most Gomphotherium, including G. connexum, were reluctant to change their diet and relied heavily on leaves, which were easier to chew than grass. It resulted in the nearly complete extinction of Gomphotherium in northern China and Central Asia by the end of Middle Miocene, the paper said. The exception was G. steinheimense, whose teeth were yet to fully adapt to the abrasive new food. "G. steinheimense had many more scratches on their molars than G. connexum," Wu said.

Fossil molars of ancient elephants. Photo provided by Wu Yan "Their active adaption to the environment helped the species to survive by better exploiting newly abundant food sources in the form of grass." It is reasonable to hypothesize that G. steinheimense, which represents an ancestral line to modern elephants, made the first step towards strongly eurytopic feeding habits, she said. The descendants of G. steinheimense later saw their low-crowned molars become high-crowned molars, which allowed them to consume cruder food as they are more powerful at grinding, she said. (BEIJING 2018-05-22 11:04:49)

|