| Location: Home > News > Events |

| LiveScience:Tiny Bird Fossil Solves Big Mystery About Life After Dinosaurs |

|

A teeny-tiny fossilized bird skeleton is helping researchers understand the explosive rate at which birds diversified after the dinosaur age, new research shows. The newfound skeleton dates back to about 62.5 million to 62 million years ago, making it the oldest known modern bird specimen in North America to live after the dinosaur-killing mass extinction, the researchers said. Its mere existence suggests that birds rapidly evolved in the 3 million to 4 million years after the dinosaurs died — much faster than previously thought, they said.

"Birds were explosively diversifying right after the end of the Cretaceous, right after the big mass extinction," said study co-author Tom Williamson, curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly (Gallery)]

Birds have a lengthy past. They began their evolutionary split from dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, about 150 million years ago. But like their scaly relatives, many bird lineages went extinct when a roughly 6-mile-long (10 kilometers) asteroid smashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

"Maybe a dozen or less lineages of birds survived," said study co-author Daniel Ksepka, curator of science at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut. (Today, there are about 40 lineages of birds that include more than 10,000 living species, he said.)

Without dinosaurs and the other extinct animals in the way, bird diversity suddenly skyrocketed, and the newfound skeleton shows just how quickly it did so, Ksepka told Live Science.

One of Tom Williamson's 12-year-old twin sons found the delicate bird fossil. (The twins are now …

Avian ancestor

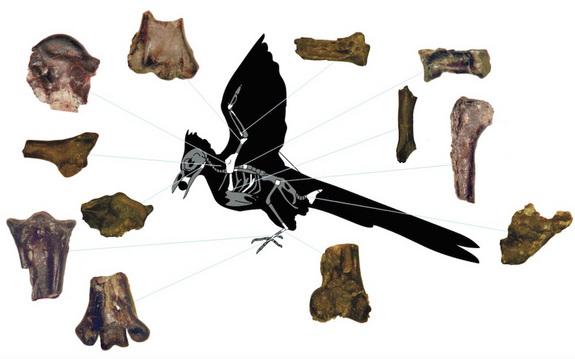

Williamson's 12-year-old twin sons found the delicate skeleton during a fossil dig in northwestern New Mexico in 2007. Williamson later excavated the fragmented bones, which are so small that the bird was likely no larger than a sparrow — smaller than the size of a human fist, he said.

The tiny bones piqued Williamson's interest, so he teamed up with Ksepka and Thomas Stidham, an avian paleontologist at the Institute for Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. The researchers analyzed the fossils, looking at 120 different size and shape characteristics.

They found that the newfound species (which they have yet to name) is part of an extinct family of birds that is closely related to owls and mouse birds — a group of small, long-tailed birds that live only in sub-Saharan Africa.

If this tiny, newfound bird was already living about 62 million years ago, it suggests that other modern birds, especially its close relatives, developed earlier than previously thought. For instance, the new evidence indicates that the mouse bird evolved some 6 million years earlier than researchers had thought, Ksepka said.

"This bird has some wide implications for the timing of the radiation [diversification] of modern birds," Ksepka said. But "to pinpoint exactly when these birds are popping up, we really need the fossil record," he added.

In 1980, other researchers, in New Zealand, discovered the fossilized skeleton of a penguin (Waimanu manneringi) that dates to between 60.5 million and 61.6 million years ago.

"Together, the new bird and Waimanu show that the diversifications of aquatic and terrestrial birds were both well underway just a few million years after the mass extinction that hit 66 million years ago," Ksepka said.

In fact, the compressed but explosive 4-million-year diversification that modern birds likely underwent after the dinosaur extinction is similar to the diversification of placental mammals, which also rapidly diversified after the nonavian dinosaurs died, he said.

The researchers presented the unpublished findings earlier this month at the 75th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference in Dallas.

Fig.1 The various skeletal pieces that researchers uncovered of the ancient bird that lived just after the age of the dinosaurs.(Katherine Dzikiewicz Bruce Museum)

From LiveScience.com (By Laura Geggel October 30, 2015 8:35 AM )

|